At Spiral Spine, we’re always keeping up with the latest research on scoliosis. We spend an incredible amount of our time working through research in order for our work to stay credible and current as we desire all of our work to be heavily based in research not guesswork. We want clients to know exercises are worthwhile and going to be beneficial for them to practice.

Our clients know this and will share research they stumble upon with us. We often have seen the research prior to their discovery; however, when an adolescent’s doctor mother sent us this hidden gem, we were instantly excited. We knew we needed to flush this information out into a much more palatable form for everyone to ingest.

From December of 2016 to December of 2017, three universities in Kosovo joined together to perform a study on the effects of combining Schroth and Pilates scoliosis exercises on adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis; this is what we at Spiral Spine have dubbed “schroth-ilates.” Upon reading this research, we were all overjoyed to see the medical community confirming what we’ve been seeing in our bodies and our clients bodies for years: combining Schroth and Pilates scoliosis exercises yields fabulous results in decreasing the symptoms of scoliosis.

While we are not Schroth practitioners, our instructors with scolisis have taken or studied the Schroth method. We regularly mix Schroth into our Pilates lessons. For example, the ideas of hanging or tractioning and padding come from the Schroth modality. We highly encourage our clients to practice Schroth and Pilates. A large portion of our adolescent clients have taken Schroth, and we regularly check in on how they are practicing their Schroth homework to ensure it’s being done correctly.

The Study Set-up

18 braced and 51 non-braced adolescent patients with idiopathic scoliosis participated in the study run through the Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Clinic at the University Clinical Center of Kosvo-Pristine. Both male and female participants’ ages ranged from 10 to 17 years old, and the participants’ Cobb angles ranged from 10 to 45 degrees. Adult and juvenile idiopathic scoliosis patients, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients with Cobb angles of over 45 degrees, congenital scoliosis patients, cervical scoliosis patients, and surgical scoliosis patients were excluded from the study.

The study consisted of learning Schroth and Pilates scoliosis exercises for one hour daily under supervision for two weeks followed by ten weeks of performing these exercises unsupervised at home. At this point, the participants were again supervised daily for two weeks to reassess the effects of the scoliosis exercises and ensure the exercises were being performed properly. This was followed by another ten week period of performing the Schroth and Pilates scoliosis exercises unsupervised at home. At the end of the twenty-four week period, the participants were once again assessed to determine the effects.

Those that conducted the study admit that scoliosis requires long-term care and that a longer follow-up with their participants or a longer study is needed to further assess the validity of the study’s findings.

The study did not utilize a control group to see what happens when no Schroth or Pilates interventions on an adolescent with idiopathic scoliosis are applied no matter if they are braced or not. It is widely understood that without interventions scoliosis will progress.

The study also does not take into account the Risser score of its participants. The Risser scale ranges 0-5 depending on the ossification (how close to fully developed the bone is) close of the iliac crests (hip bones), with a higher score equaling more ossification. Those that conducted the study admit skeletal maturation could be a factor in the results of the study. If they were to do another study they would use the Risser scale to track skeletal maturation and divide the results accordingly.

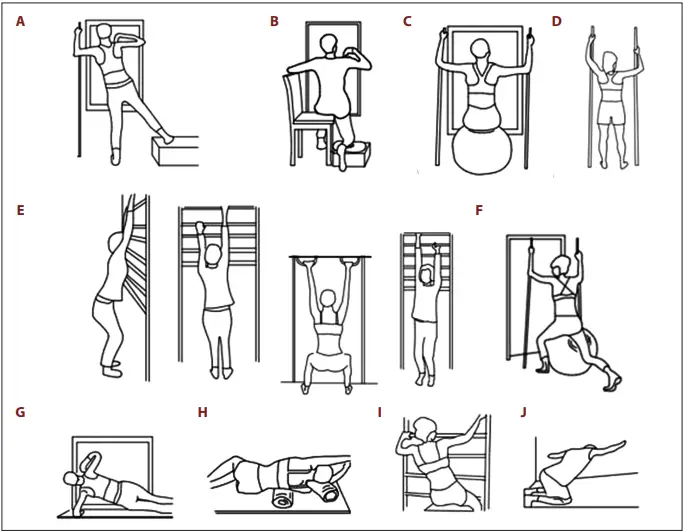

The Schroth Exercises

Participants with thoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbar curves were given different Schroth exercises to target their specific needs. They were expected to complete their Schroth exercises daily for 30 minutes. Below is a listing of what Schroth exercises were given to each participant followed by an explanation of each exercise.

Thoracic patients were given “thoracic spine correction, hanging, stretching of the weak side (concave side of the scoliosis curve), sitting on the Swiss ball, strengthening the back muscles and side stretching (concave side).” These are the Shroth exercises A, E, H, I, and J shown in the chart below.

Thoracolumbar patients (including multi-curved patients) were given : basic correction sitting, self-correction exercise in front of the mirror, hanging, stretching the weak side (concave side of the scoliosis curve), strengthening the back muscles, and thoracolumbar spine correction.” These are the Shroth exercises C, D, E, H, I, and J shown in the chart below.

Lumbar patients were given “lumbar spine correction, lifting the pelvis laterally, hanging, stretching the weak side (concave side of the scoliosis curve), strengthening the back muscles and side stretching (concave side).” These are the Shroth exercises B, E, G, H, and J shown in the chart below.

A – Thoracic spine correction

B – Lumbar spine correction

C – Basic correction sitting

D – Self-correction in front of mirror

E – Hanging/Traction

F – Thoracolumbar spine correction

G – Lateral pelvic lift/Side plank

H – Weak (concave) side stretch

I – Thoracic spine correction sitting

J – Strengthen and stretch weak (concave) side

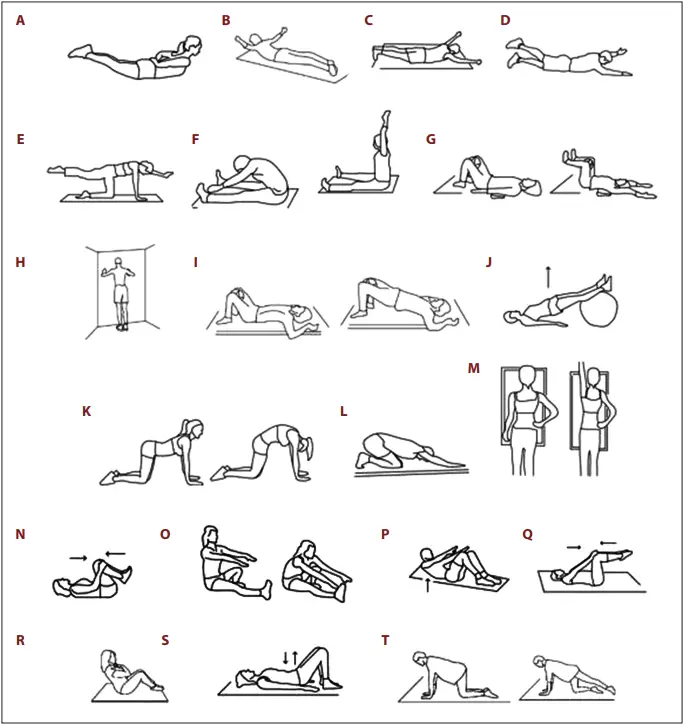

The Pilates Exercises

Participants with thoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbar curves were given different Pilates exercises to target their specific needs. All participants were expected to complete their Pilates exercises daily for 30 minutes. Unlike the Schroth exercises, all Pilates exercises were given to all participants. The Pilates exercises targeted spine and trunk strengthening and stretching as well as limb strengthening and stretching. Below is an explanation of each exercise.

A – Spinal extension prone arms reaching like in Double Leg Kick

B – Spinal extension arms in T prone

C – Spinal extension arms in Y prone

D – Arm and leg raise in prone/Swimming

E – Quadruped arm and leg raise/Bird dogs – holding

F – Back hyperextension with hands forward/Spine Stretch Forward

G – Flex shoulder and leg in supine/Double Toe Taps with flexion and extension

H – Wall scapular push-ups

I – Bridge

J – Bridge on Ball

K – Cat/Cow

L – Child’s Pose

M – Side Stretch stretching concave side

N – Lumbar spine stretch rocking side-to-side and circles both ways

O – Hamstring Stretch

P – Abdominal Curl

Q – Double Leg Abdominal Press

R – Sit ups w/ Crossed Arms

S – Pelvic Floor Pulses

T – Quadruped arm and leg raise/Bird dogs – tap and lift

The Results

The study consisted of measuring Cobb angle, axial vertebral rotation, chest expansion, spinal flexibility in flexion, and quality of life at the start of the study, 1mid-study/twelve weeks, and at the end of the study/twenty four weeks.

Cobb Angle

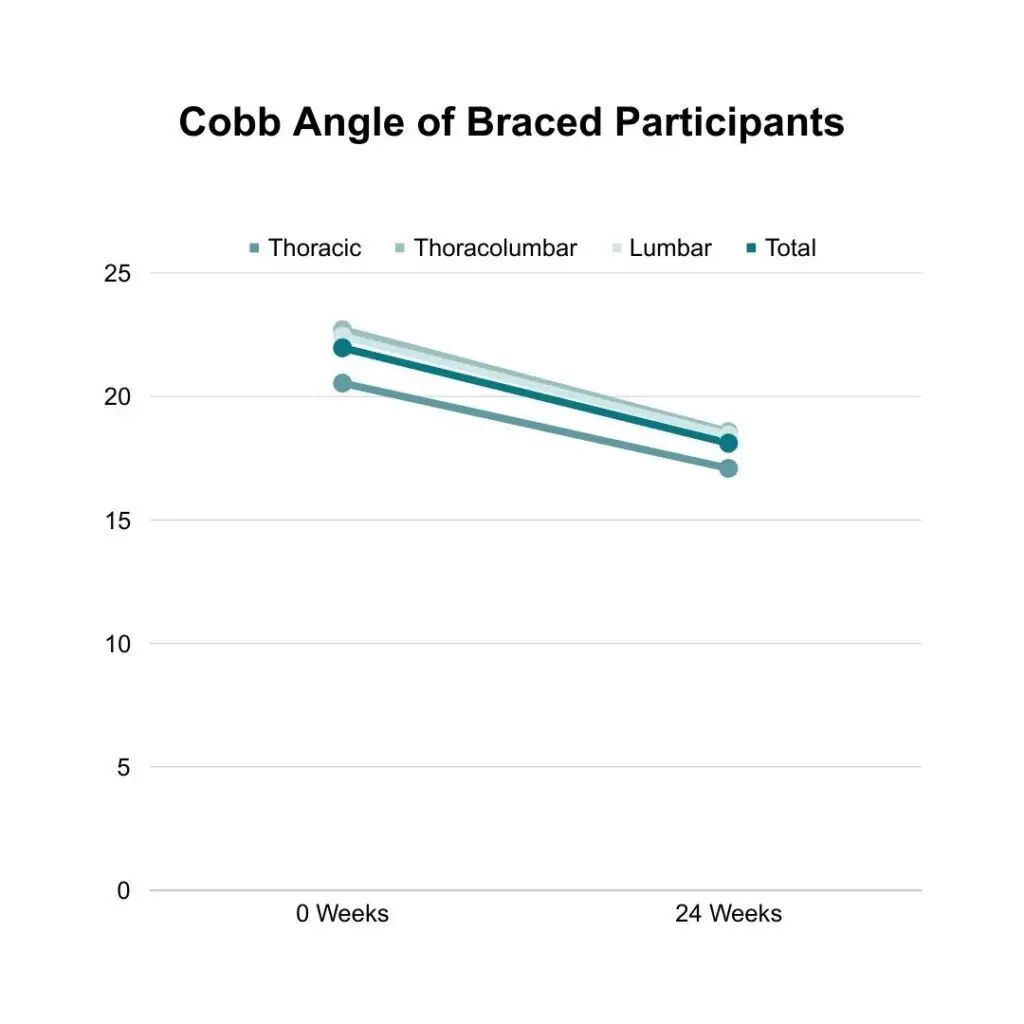

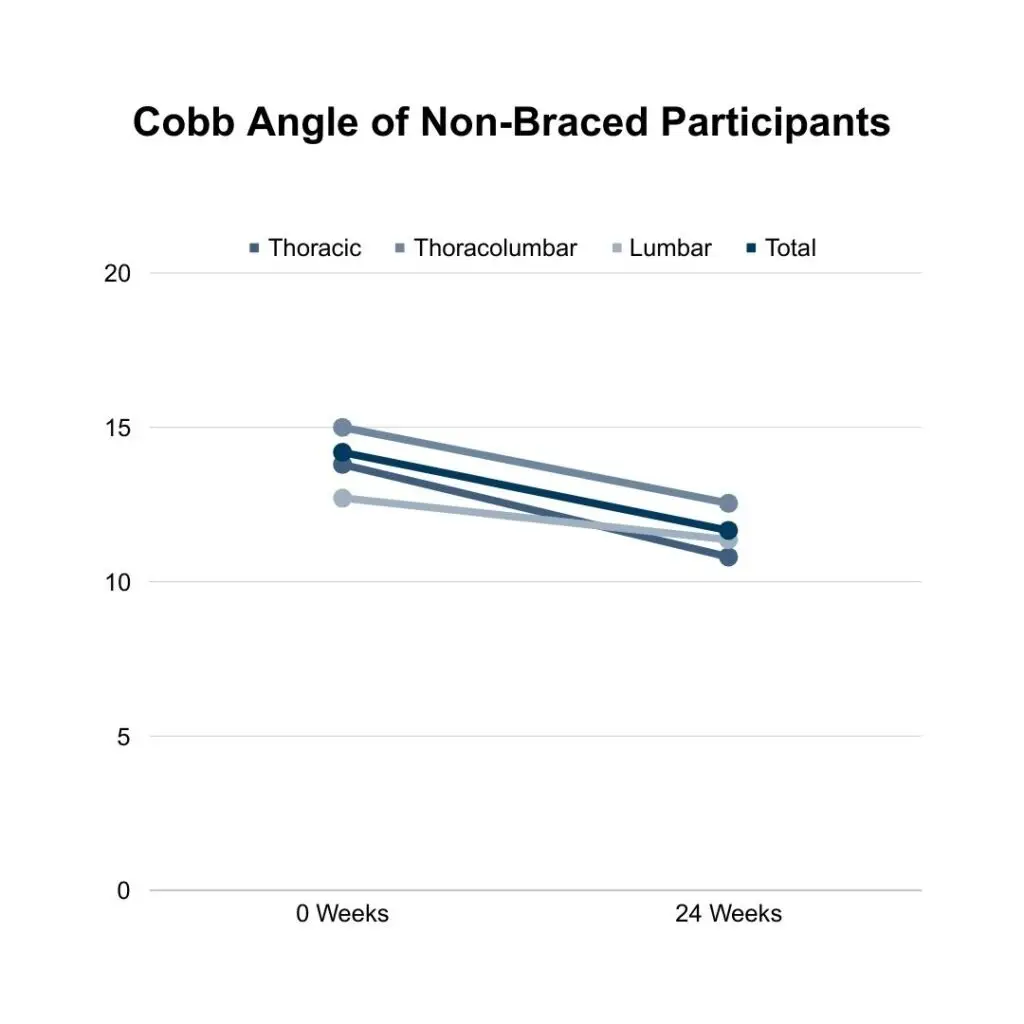

Cobb angle was measured by posterior and lateral x-rays. For braced participants, the time prior to x-ray out of brace was within the daily allotted time. An improvement is seen as a decrease in Cobb angle degree.

Braced participants saw decreased Cobb angles in all three measured regions: thoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbar. In the thoracic region, the participants’ mean Cobb angle decreased 3.45 degrees from 20.54 degrees to 17.09 degrees. In the thoracolumbar region, the participants’ mean Cobb angle decreased 4.14 degrees from 22.71 degrees to 18.57 degrees. In the lumbar region, the participants’ mean Cobb angle decreased 4.00 degrees from 22.44 degrees to 18.44 degrees. When averaged together, braced participants’ Cobb angle decreased 3.86 degrees from 21.97 degrees to 18.11 degrees.

Non-braced participants saw decreased Cobb angles in all three measured regions: thoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbar. In the thoracic region, the participants’ mean Cobb angle decreased 3.00 degrees from 13.80 degrees to 10.80 degrees. In the thoracolumbar region, the participants’ mean Cobb angle decreased 2.48 degrees from 15.00 degrees to 12.52 degrees. In the lumbar region, the participants’ mean Cobb angle decreased 1.35 degrees from 12.71 degrees to 11.36 degrees. When averaged together, braced participants’ Cobb angle decreased 2.53 degrees from 14.19 degrees to 11.66 degrees.

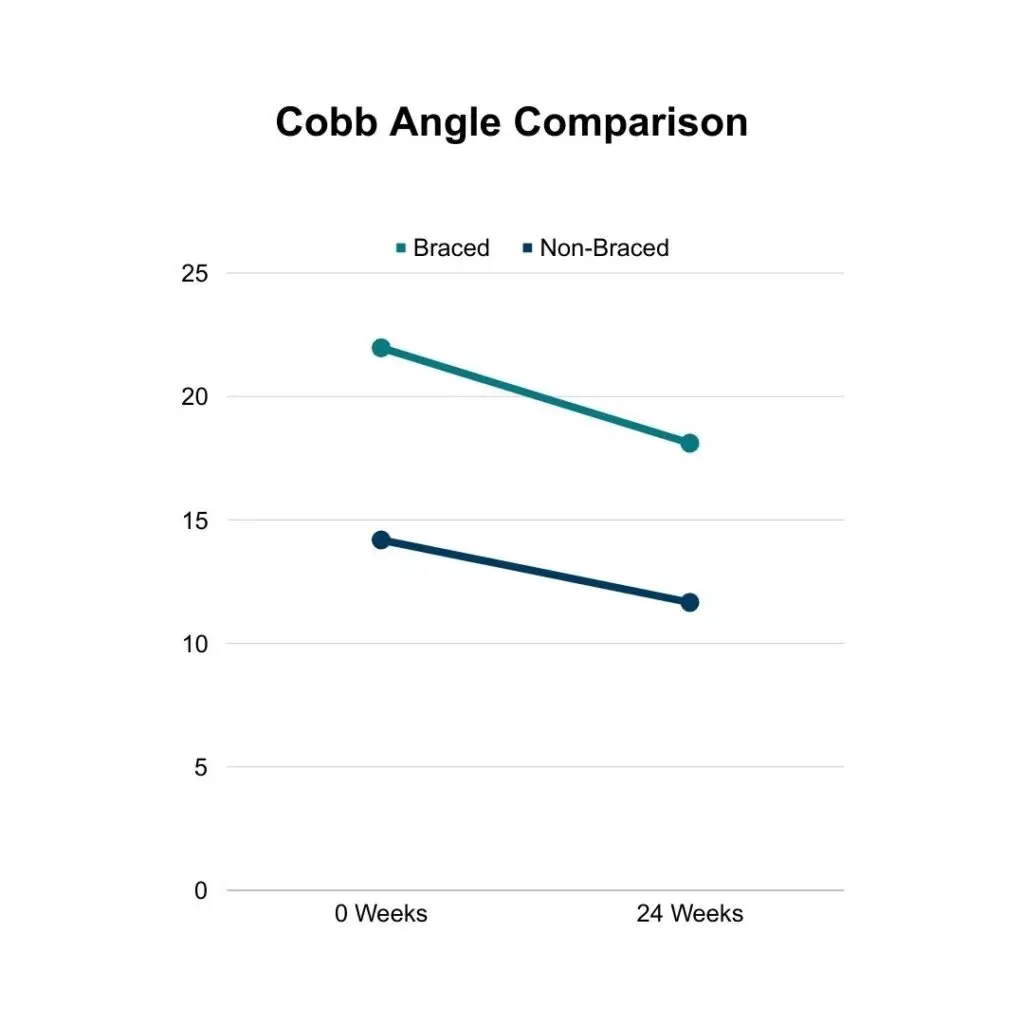

Both braced and non-braced participants saw decreases in their Cobb angles no matter the location of the curvature. Greater Cobb angle decreases were seen in braced participants. Braced participants’ average Cobb angle decreased 3.86 degrees from 21.97 degrees to 18.11 degrees, and non-braced participants’ average Cobb angle decreased 2.53 degrees from 14.19 degrees to 11.66 degrees.

While that seems to indicate wearing a corrective brace will provide greater aid in Cobb angle decrease, it’s important to note that non-braced participants began with a lower average Cobb angle and, therefore, had less of a range to decrease. The difference in degree decrease is not statistically significant because the difference is so small (1.33 degrees) and the same Cobb angle range is not being compared in each group (braced higher and non-braced lower). The important information to glean is that no matter if one is braced, the Schroth and Pilates exercises decreased all of the participants’ Cobb angles.

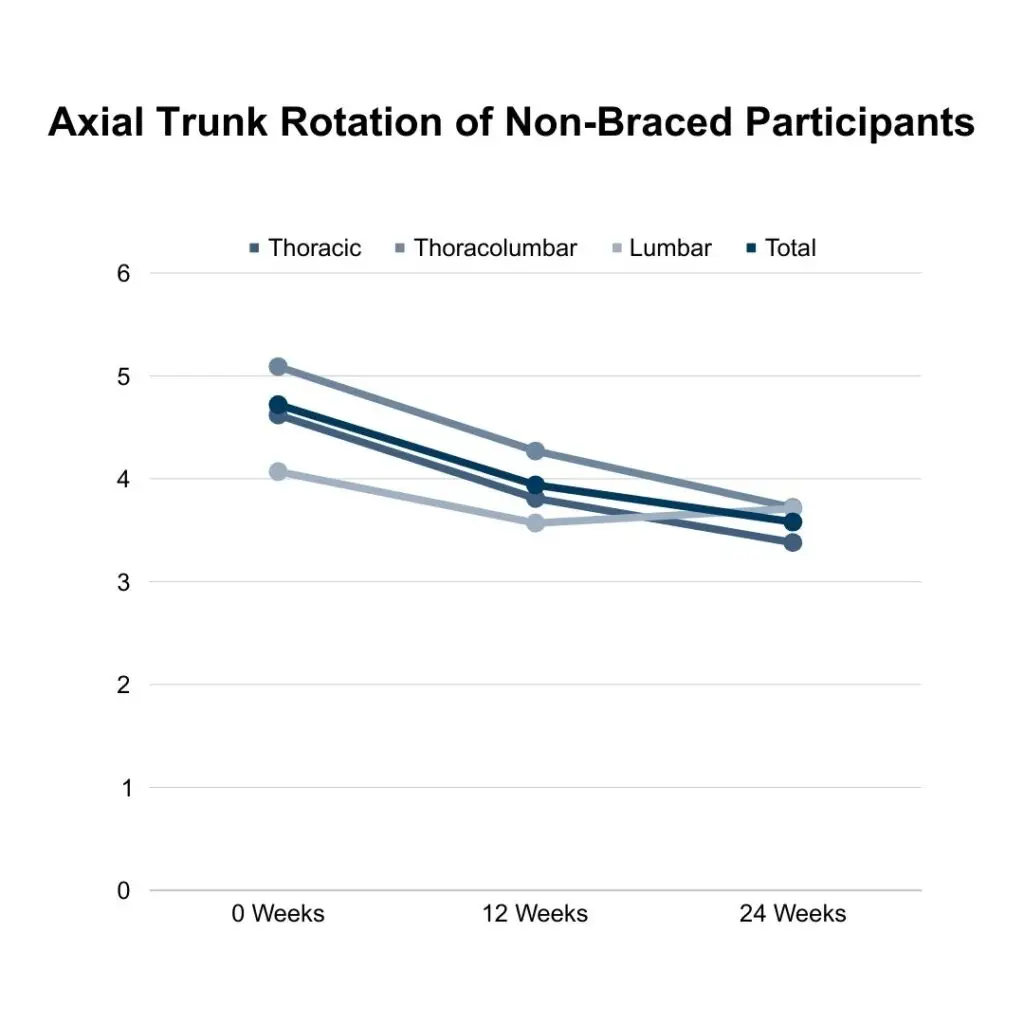

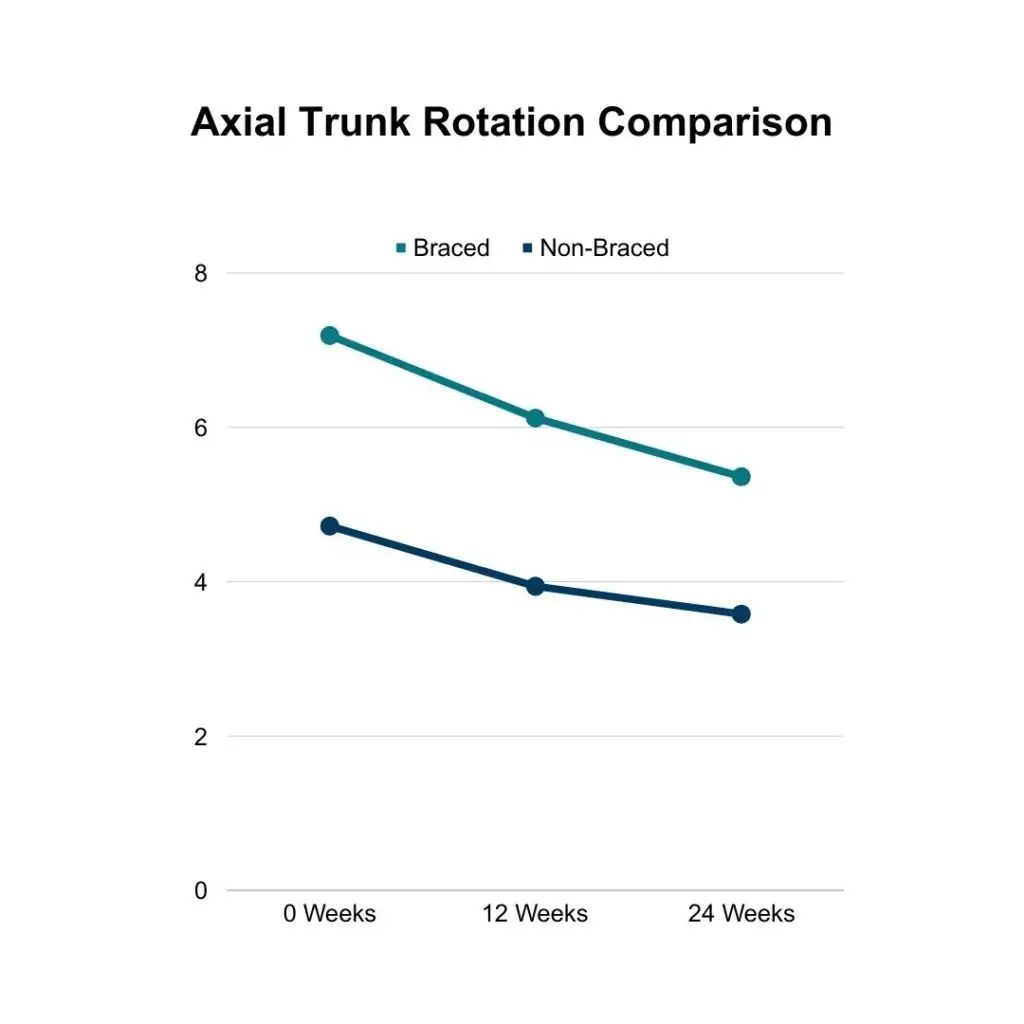

Axial Trunk Rotation

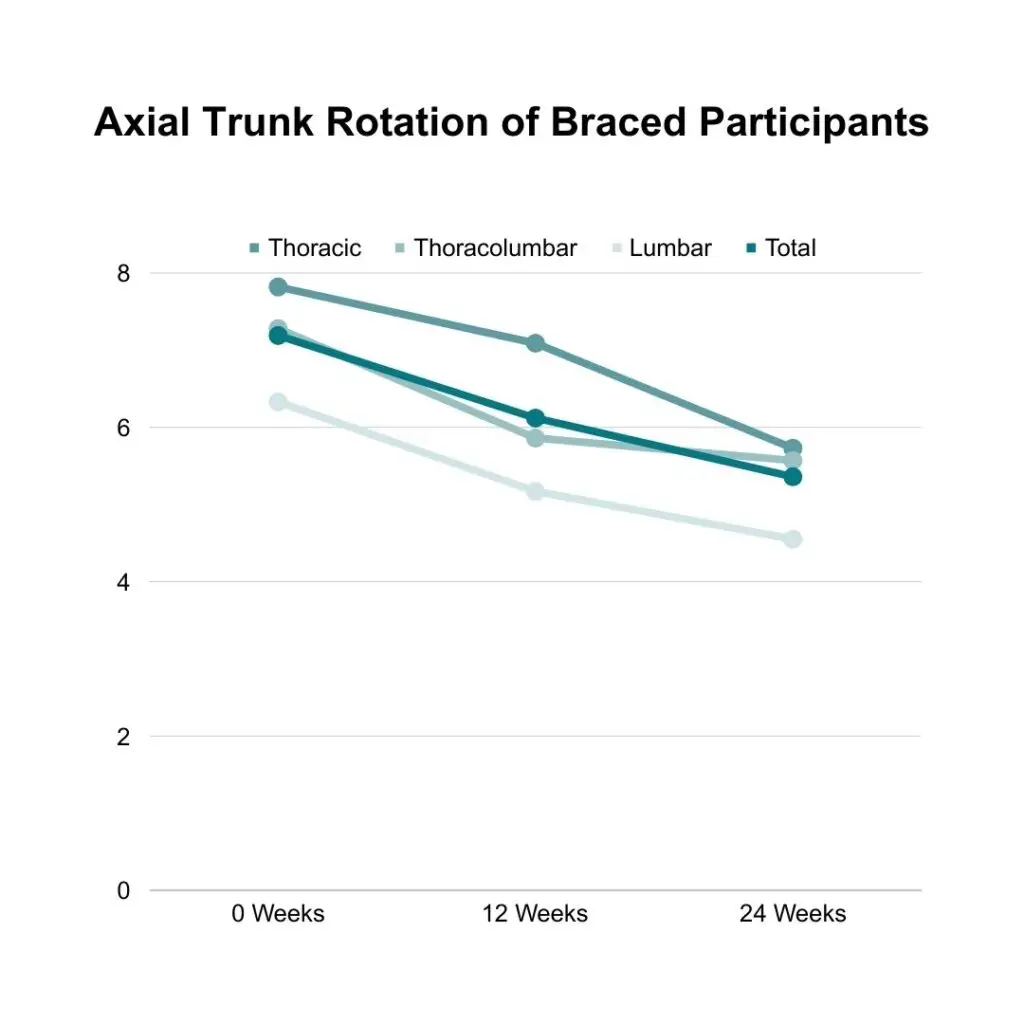

Axial trunk rotation (ATR), also known as axial vertebral rotation, was measured using a scoliometer. Read about how to use a scoliometer to track your scoliosis using a scoliometer here. An improvement is seen as a decrease in ATR degree.

Braced participants saw decreased ATR in all three measured regions: thoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbar. In the thoracic region, the participants’ mean ATR decreased 2.09 degrees from 7.82 degrees to 5.73 degrees. In the thoracolumbar region, the participants’ mean ATR decreased 1.71 degrees from 7.28 degrees to 5.57 degrees. In the lumbar region, the participants’ mean ATR decreased 1.78 degrees from 6.33 degrees to 4.55 degrees. When averaged together, braced participants’ ATR decreased 1.83 degrees from 7.19 degrees to 5.36 degrees.

Non-braced participants saw decreased ATR in all three measured regions: thoracic, thoracolumbar, and lumbar. In the thoracic region, the participants’ mean ATR decreased 1.24 degrees from 4.62 degrees to 3.38 degrees. In the thoracolumbar region, the participants’ mean ATR decreased 1.37 degrees from 5.09 degrees to 3.72 degrees. In the lumbar region, the participants’ mean ATR decreased 0.36 degrees from 4.07 degrees to 3.71 degrees. When averaged together, non-braced participants’ ATR decreased 1.14 degrees from 4.72 degrees to 3.58 degrees.

Both braced and non-braced participants saw decreases in their ATR no matter the location of the curvature. Greater ATR decreases were seen in braced participants. Braced participants’ average ATR decreased 1.83 degrees from 7.19 degrees to 5.36 degrees, and non-braced participants’ average ATR decreased 1.14 degrees from 4.72 degrees to 3.58 degrees.

These numbers are consistent with the Cobb angle results, as we expected. Those who wore a brace decreased 0.69 degrees more than those who did not, which is even less significant than the difference seen in the Cobb angle decrease. Again, the important information to glean is that no matter if one is braced, the Schroth and Pilates exercises decreased all of the participants’ ATR.

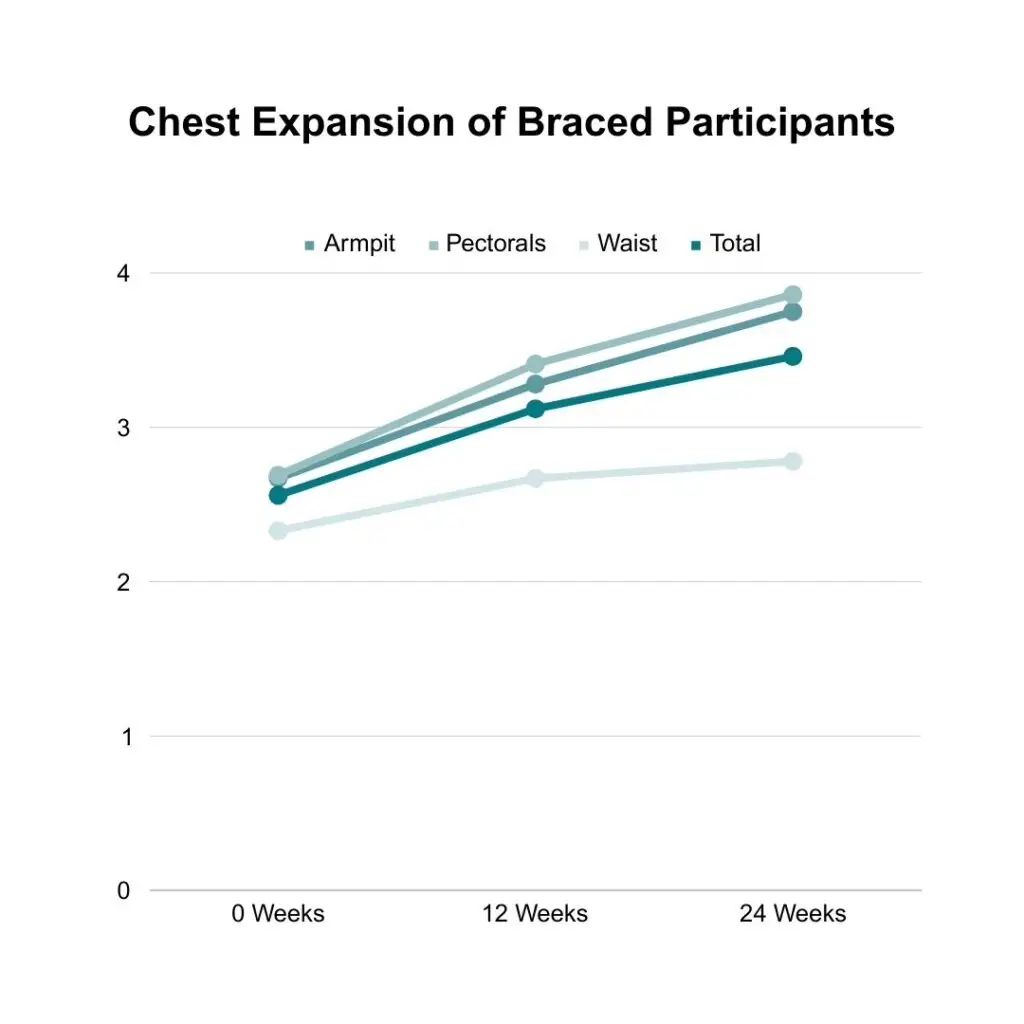

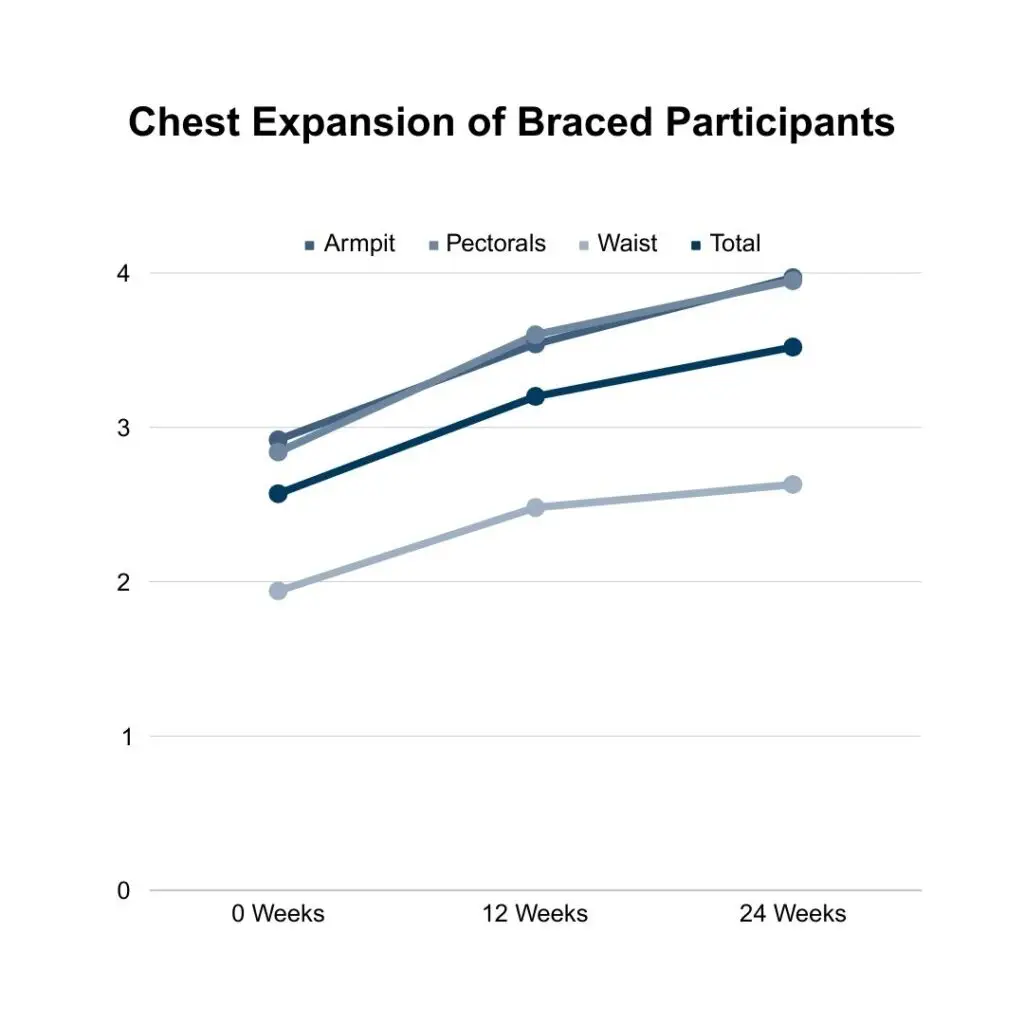

Chest Expansion

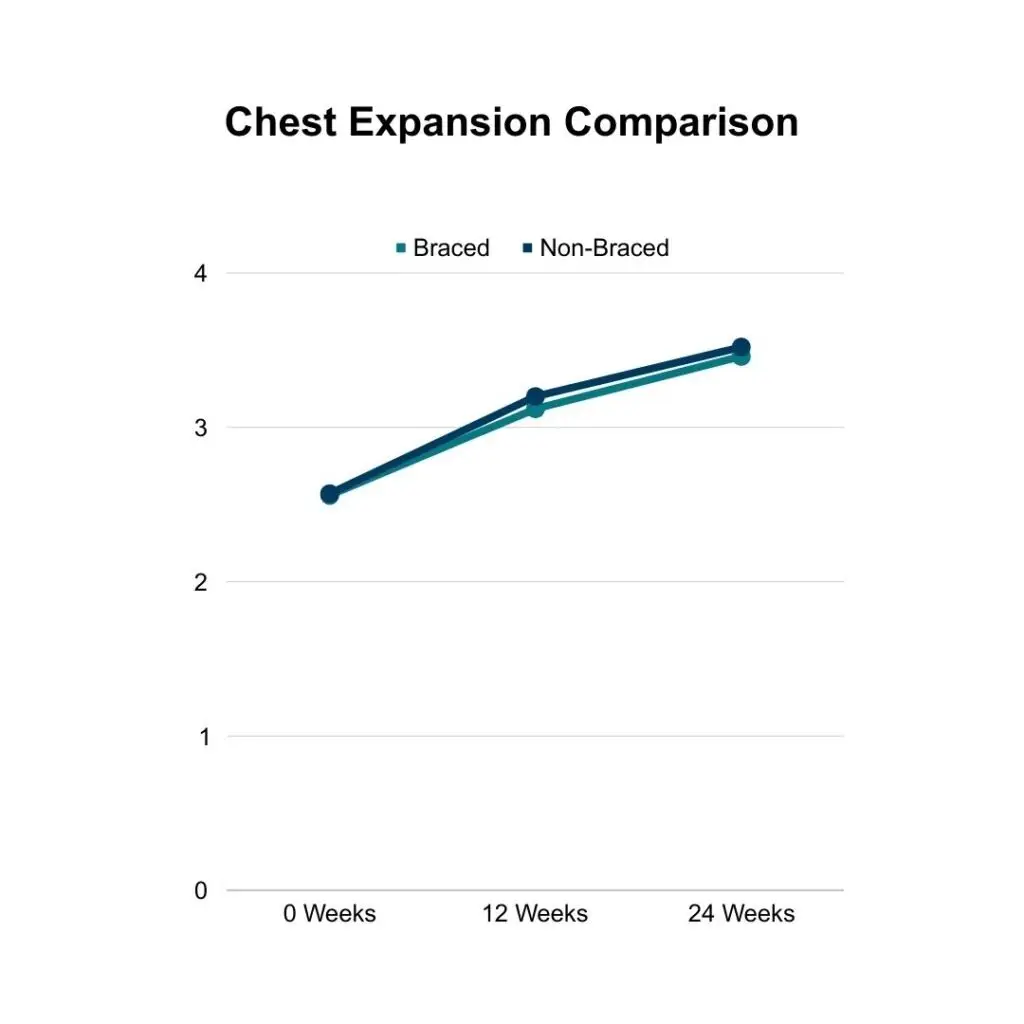

Chest expansion was measured in centimeters while participants were standing using a measuring tape at the deepest point of inhalation in three locations: sub-axillary (under the armpits), nipple line (around the pectorals), waist (narrowest part of torso). An improvement is seen as an increase in how many centimeters the chest can expand.

Braced participants saw increased chest expansion in all three measured regions: under armpits, around pectorals, and around waist. Under the armpits, the participants’ mean chest expansion increased 1.08 cm from 2.67 cm to 3.75 cm. Around the pectorals, the participants’ mean chest expansion increased 1.17 cm from 2.69 cm to 3.86 cm. Around the waist, the participants’ mean chest expansion increased 0.45 cm from 2.33 cm to 2.78 cm. When averaged together, braced participants’ average chest expansion increased 0.90 cm from 2.56 cm to 3.46 cm.

Non-braced participants saw increased chest expansion in all three measured regions: under armpits, around pectorals, and around waist. Under the armpits, the participants’ mean chest expansion increased 1.05 cm from 2.92 cm to 3.97 cm. Around the pectorals, the participants’ mean chest expansion increased 1.11 cm from 2.84 cm to 3.95 cm. Around the waist, the participants’ mean chest expansion increased 0.69 cm from 1.94 cm to 2.63 cm. When averaged together, non-braced participants’ average chest expansion increased 0.95 cm from 2.57 cm to 3.52 cm.

Both braced and non-braced participants saw increases in their chest expansion. Greater chest expansion increases were seen in non-braced participants. Braced participants’ average chest expansion increased 0.90 cm from 2.56 cm to 3.46 cm, and non-braced participants’ average chest expansion increased 0.95 cm from 2.57 cm to 3.52 cm.

Parents often ask if their child wearing a corrective brace for scoliosis will negatively impact their child’s ability breathe. This data shows that while non-braced participants saw greater increases in chest expansion they only marginally did so; 0.05 cm is 5%. This data confirms that if you choose to wear a corrective brace for your scoliosis it is imperative that you are doing Schroth and Pilates exercises to maintain and improve your chest expansion.

Trunk Flexion

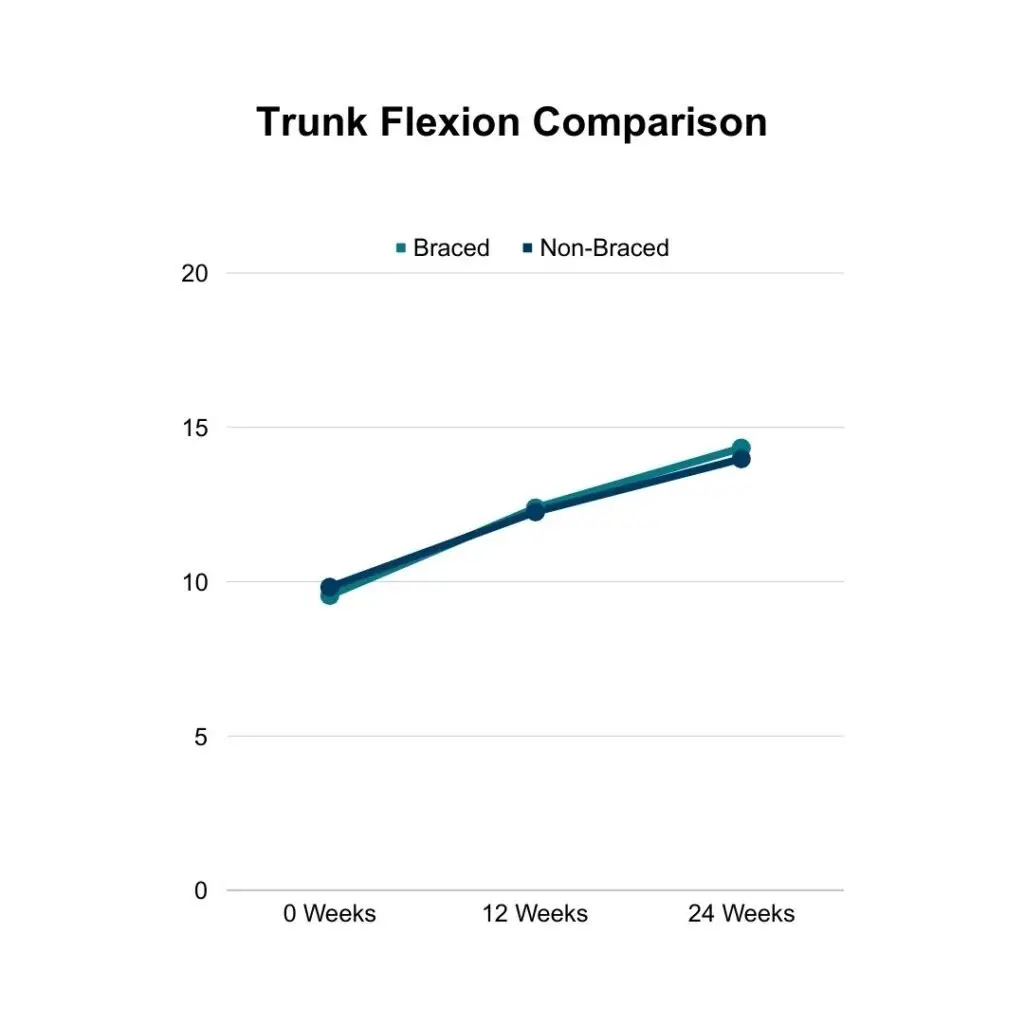

Trunk flexion was also measured using a measuring tape. The distance between vertebra C7 to vertebra S2 was measured in centimeters as participants curled forward as if they were trying to touch their toes; this prevented participants from compensating for tight hamstrings or other areas. An improvement is seen as an increase in how many centimeters the trunk/spine is able to flex.

Both braced and non-braced participants saw increases in their trunk flexion. Braced participants’ trunk flexion increased 4.78 cm from 9.55 cm to 14.33 cm. Non-braced participants’ trunk flexion increased 4.16 cm from 9.82 cm to 13.98 cm.

When considering corrective bracing for their children, parents often ask if the brace will hinder spinal mobility. This data shows that the exact opposite is true if proper attention is given to preventing a hindrance. If you choose to wear a corrective brace for your scoliosis it is important that you are doing Schroth and Pilates exercises to maintain and improve your trunk flexibility.

Quality of Life

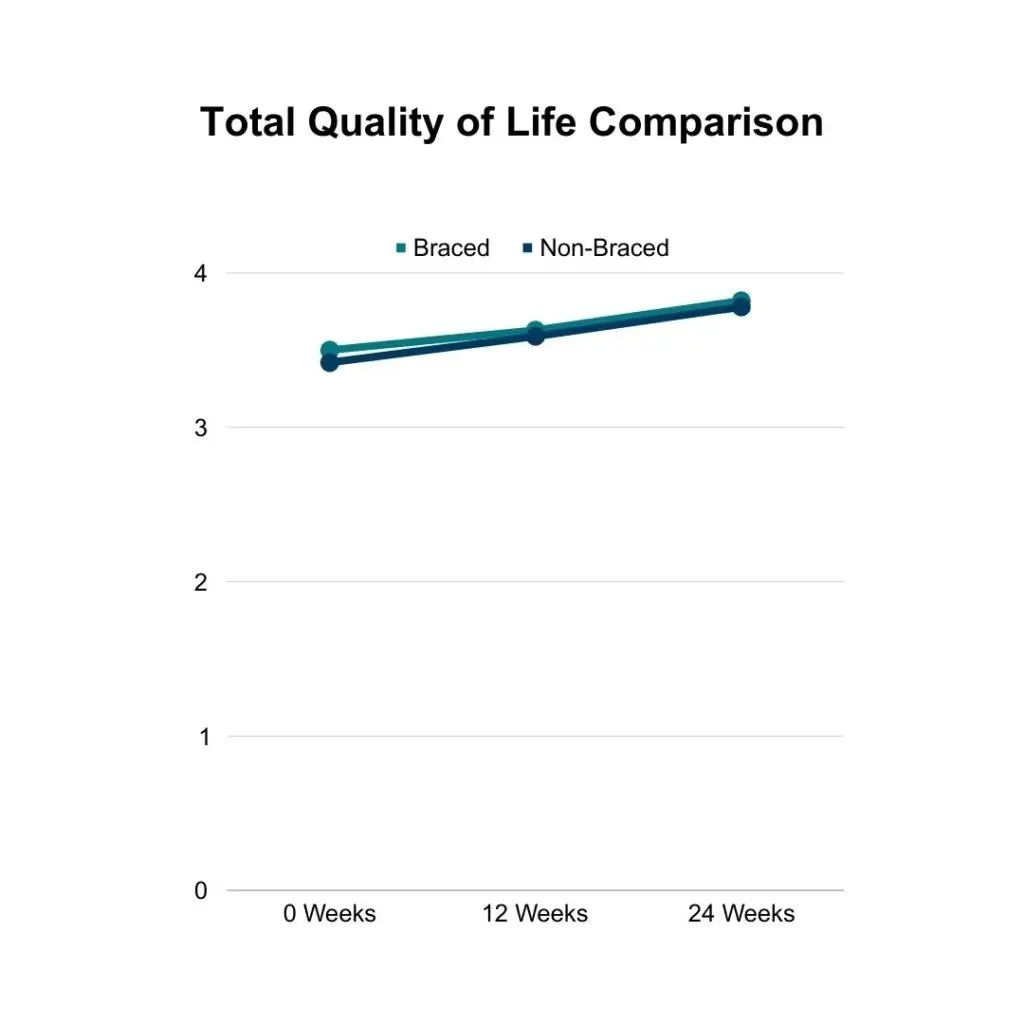

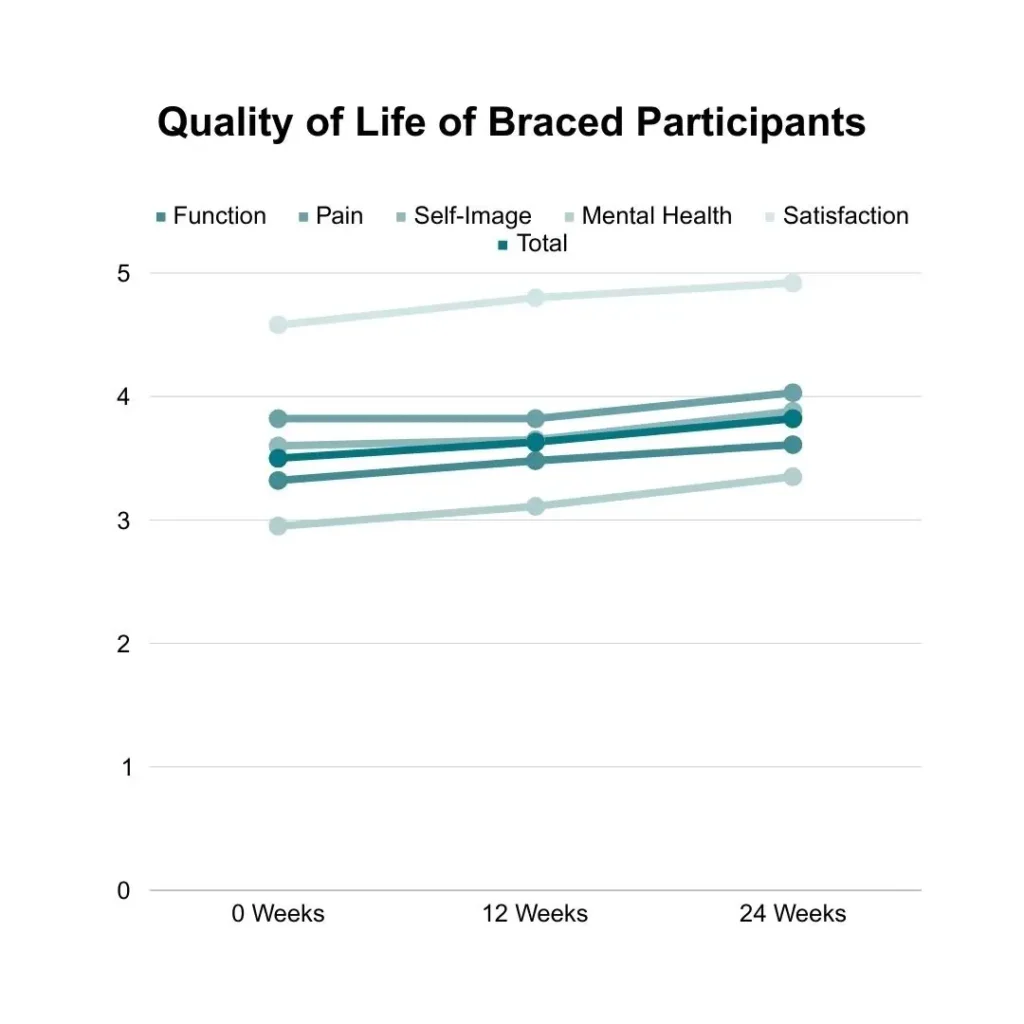

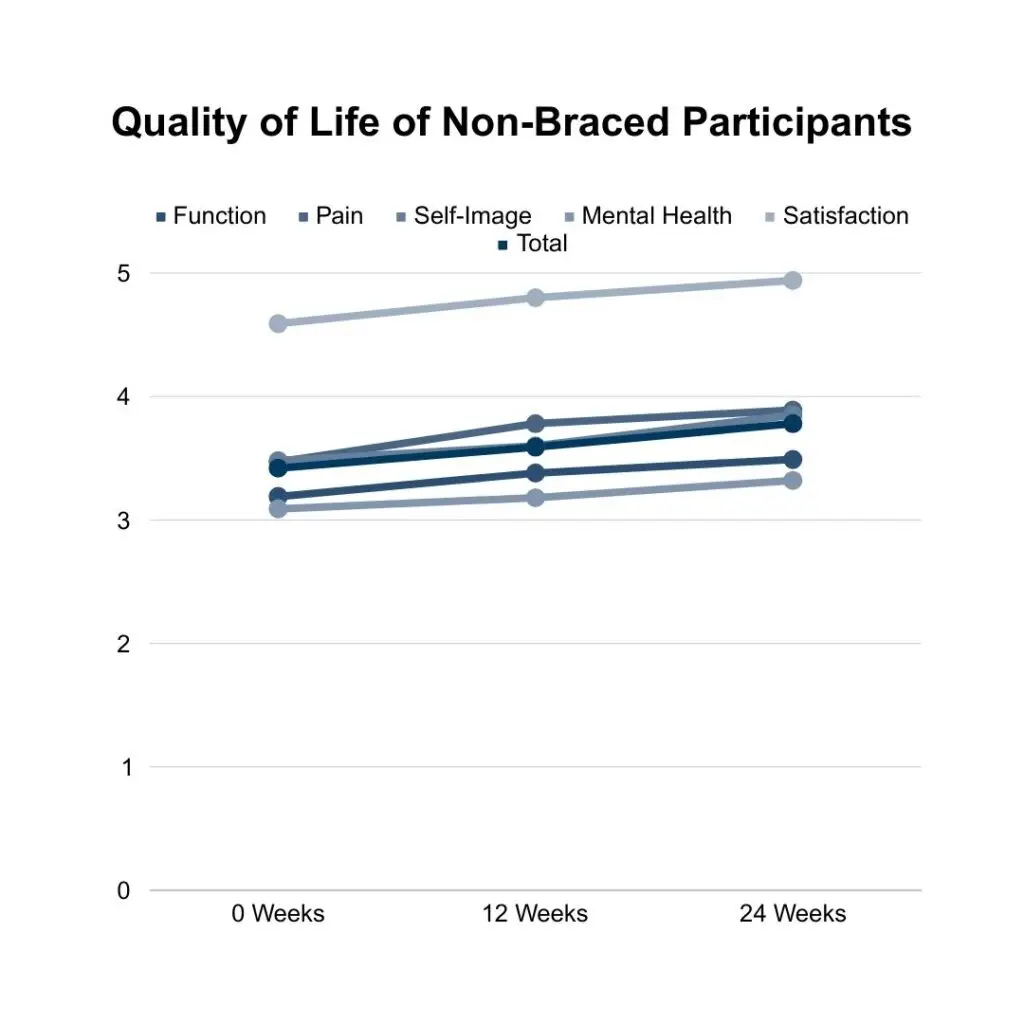

Quality of life (QoL) was measured using the SRS-22r; this is a 22-question form that measures five facets of daily life: functionality, pain levels, self-image, mental health, and satisfaction with treatment. According to how the SRS-22r is scored, an increase in score is associated with improvement in each facet. The range of scores in each category is 1 (lowest QoL) to 5 (highest QoL). This is counterintuitive when it comes to pain levels, but an increased score in pain does denote a decrease in a participant’s pain levels.

Braced participants saw increased quality of life in all five measured regions. Participants’ functionality increased 0.29 from 3.32 to 3.61. participants’ level of pain increased 0.21 from 3.82 to 4.03. Participants’ self-image increased 0.28 from 3.60 to 3.88. Participants’ mental health increased 0.40 from 2.95 to 3.35. Participants’ satisfaction of their treatment increased 0.34 from 4.58 to 4.92. When averaged, braced participants QoL increased 0.32 from 3.50 to 3.82.

Non-braced participants saw increased quality of life in all five measured regions. Participants’ functionality increased 0.30 from 3.19 to 3.49. participants’ level of pain increased 0.42 from 3.47 to 3.89. Participants’ self-image increased 0.37 from 3.48 to 3.85. Participants’ mental health increased 0.23 from 3.09 to 3.32. Participants’ satisfaction of their treatment increased 0.35 from 4.59 to 4.94. When averaged, non-braced participants QoL increased 0.36 from 3.42 to 3.78.

Both braced and non-braced participants saw increases in their QoL according to the SRS-22r. Braced participants QoL increased 0.32 from 3.50 to 3.82, and non-braced participants QoL increased 0.36 from 3.42 to 3.78.

Both braced and non-braced participants scored the highest in satisfaction of their treatment plans before and after the study. It is important to note that the satisfaction score was the highest score in both populations and also the only score to break 4.00 other than braced participants final pain levels (4.03). So, even if you feel that your current care plan is alright, you might want to look at adding in Schroth and Pilates exercises to your scoliosis treatment.

When considering having their child wear a corrective scoliosis brace, parents should consider their children’s QoL. This data shows that despite being braced, braced participants experienced an increase in their QoL throughout the study. Bracing can negatively impact one’s QoL, which we have seen firsthand with new clientele at Spiral Spine and other research has shown (2). The results of this study show that bracing in combination with Schroth and Pilates exercises does not have to negatively impact a child’s QoL and that regularly completing Schroth and Pilates exercises positively impacts a child’s QoL, which aligns with what we have experienced in our studio.

The Conclusions

After twenty four weeks of combining Schroth and Pilates exercises to care for braced and non-braced participants’ scoliosis, Cobb angle and axial trunk rotation decreased with chest expansion, trunk flexibility, and quality of life increased. The Schroth method was originally developed to help those with severe scoliosis curves; however, the results of this study show that the Schroth method when combined with the Pilates method can also help those with mild and moderate scoliosis curves.

The largest take aways from this overwhelming amount of data (which was simplified for the sake of legibility of this blog) are as follows:

- Movement helps all aspects of one’s life in unfused adolescents diagnosed with idiopathic scoliosis, no matter curvature location or degree or whether they wear a corrective brace. Specifically, Schroth and Pilates movement.

- When considering bracing for scoliosis care, movement is key in order to prevent any of the negatives normally associated with the practice of bracing.

At Spiral Spine Pilates, we aim to be the movement portion of our clients’ scoliosis care. We endeavor to be our clients’ safe place for corrective movement and would love to be a part of your scoliosis journey as well. If you would like help finding the best exercises for your scoliosis, book a lesson with one of us! We work with people locally and across the globe daily to care for their scoliosis.

(1) Rrecaj-Malaj, Shkurta & Beqaj, Samire & Krasniqi, Valbona & Qorolli, Merita & Tufekcievski, Aleksandar. (2020). Outcome of 24 Weeks of Combined Schroth and Pilates Exercises on Cobb Angle, Angle of Trunk Rotation, Chest Expansion, Flexibility and Quality of Life in Adolescents with Idiopathic Scoliosis. Medical Science Monitor Basic Research. 26. 10.12659/MSMBR.920449.

(2) Piantoni, L., Tello, C.A., Remondino, R.G. et al. Quality of life and patient satisfaction in bracing treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis 13, 26 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13013-018-0172-0

Jennifer Stark is a Nationally Certified Pilates Teacher, Certified Integrated Movement Specialist, and Certified Kinesiology Taping Practitioner. Jennifer has worked alongside Erin Myers on multiple scoliosis education endeavors including Analyzing Scoliosis, I Have Scoliosis; Now What?, and the Scoliosis Retreat which is held regularly at Spiral Spine Pilates Studio.

Jennifer Stark is a Nationally Certified Pilates Teacher, Certified Integrated Movement Specialist, and Certified Kinesiology Taping Practitioner. Jennifer has worked alongside Erin Myers on multiple scoliosis education endeavors including Analyzing Scoliosis, I Have Scoliosis; Now What?, and the Scoliosis Retreat which is held regularly at Spiral Spine Pilates Studio.