Most clients come to me and ask, “what is scoliosis?” They’ve been diagnosed, but they don’t actually understand what it is. Scoliosis is a lateral curvature of the spine of 10 degrees or more. This means the spine is bending sideways, not forwards and backwards. That’s the definition. Sounds simple, right? Look at the spine, see that it has a curve that meets that criteria, and boom—it’s diagnosed as scoliosis by a doctor.

While other characteristics like uneven muscle development, vertebral rotation, and uneven shoulders and hips may be present, that’s not what diagnoses you as having scoliosis. An overly rounded spine going forward or backward may also be present while having scoli, but again, that’s not what diagnoses you as having scoliosis.

Unfortunately, scoli can be much more complex than that simple definition of a lateral curvature of the spine of 10 degrees or more. For example, it can be caused by an almost endless number of circumstances or other medical conditions. But oftentimes, scoliosis is polycausational, meaning it developed due to a myriad of reasons. Doctors and researchers have spent oodles of money and time attempting to determine the root causes of scoliosis. But even with all that research, the question of “Where did this come from?” still doesn’t have a definitive answer in many cases and the diagnosis of scoliosis is generic and often a not very insightful diagnosis as to the cause of the curvature.

What is scoliosis?

Let me reiterate, scoliosis is medically defined as a side-to-side bending of the spine 10 degrees or greater. If what’s presenting in the spine doesn’t adhere to a sideways bend of the spine of 10 degrees or more, it’s not scoliosis; it’s something else.

I can’t count the number of times I’ve had first-time clients tell me they (or their doctor, coach, parents, etc.) think they have scoliosis, only to be met with a spine with no lateral curvature. They simply don’t fit into the medical definition of what scoliosis is. These clients can’t even answer the question “what is scoliosis?” If you don’t know what something is, how are you going to address it? Being able to answer what is scoliosis when you’re diagnosed with scoli empowers you to know what is going with your body and leads you to make better choices in your care for it.

Scoliosis Jargon

There are a bunch of terms that we use when talking about scoli: concave, convex, apex, major, minor, Cobb angle, scoliometer, idiopathic, functional, congenital, and more. Honestly, it takes a while for people to know where their scoli is, and how to talk about it. By defining these words, I’m hoping to take some of the guesswork out of your equation and empower you to be able to advocate for yourself or your loved one with scoli.

Concave vs. Convex

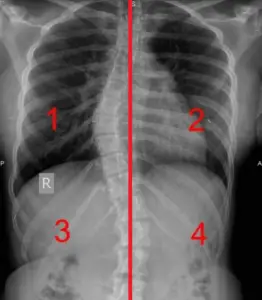

Every scoliosis curve has a concave and a convex side. They are opposing sides of the curve as seen in the image below. Most scoli spines have multiple curves and therefore have multiple concave and convex parts of the spine.

I have a silly way of remembering this. I visualize an actual cave. If I’m inside the cave, it’s rounded over my head. So, if I’m “inside” the round part of a curve, I’m in the concave portion. If I’m not “inside” the curve, I’m outside of it. That means I have to be in the convex part.

I’m going to use the picture sent to me by a young woman in Asia I used in the blog post here to describe this further.

The numbers 2 and 3 are the concave portions of the curves and numbers 1 and 4 are the convex portions of the curves. Can you see how 2 and 3 are “inside the cave” of the curve? Can you visualize how 1 and 4 are going out?

Most people’s muscles are beefier and more built up on the convex portions of their curve (1 and 4 in the picture above). While they are the longer muscles, they’re usually the workhorse muscles and have been attempting to hold the back upright for many years. The muscles inside the concave portion are shorter and usually more atrophied, which would be 2 and 3 in the picture above.

Apex

The apex of the curve is simply the vertebral level where the curve is the largest. Again, you can have multiple apexes if you have multiple curves, which is normal. In the image above, count down 8 from the top to find the first apex and then count down to 13 to find the second apex of my client.

Major curves vs. minor curves

Let’s reference back to the same image, draw an imaginary line down the middle of the body and see which curve is the furthest from this line. The major curve is the largest curve, and the minor curve or curves are the smaller ones.

This client’s major curve is on the top labeled 1 and 2, and her minor curve is on the bottom labeled 3 and 4.

Cobb angle

A Cobb angle is the precise degree of measurement of the lateral scoliotic curve, as determined by the Cobb Method. A specialist will take an X-ray of the spine and make two straight lines on the top and bottom of the curve. The angle where those lines intersect is the Cobb angle, or the exact lateral degree of the scoliotic curve. This is how scoliosis is diagnosed and tracked by a person’s doctor. Again, people will have as many Cobb angles as they do curves.

This image is an X-ray of my spine where you can see those lines drawn onto the X-ray by a specialist. I know there are a few numbers here, but look at the lower number associated with each curve. When this X-ray was taken, the Cobb Angle measurement of my top or major curve was 35.1 degrees and my bottom or minor curve was 13.3 degrees.

Axial Vertebral Rotation & the Scoliometer

Scoliosis can cause the spine to rotate, and the spine often takes the ribs along for the ride. Axial vertebral rotation is exactly what it sounds like: spinal rotation, like a twist. Rotation is extremely common in scoliotic clients’ bodies. Honestly, it’s less common to not have rotation. If there is rotation in a scoli curve, it will usually be wherever the apex of the curve is. The rotation will go toward the front of the body in the concave part of the curve. In other words, it’s as if the rib cage is rotating further into the “cave” created by the concave side.

Axial vertebral rotation can be measured by a tool called a scoliometer. Research shows that one’s Cobb Angle (measured by an X-ray) and vertebral rotation (measured by a scoliometer) are positively correlated. Meaning, if you have someone measure your back with a scoliometer before and after an activity and notice a decrease in degree, you can deduce that your scoli likely got a little straighter. Tracking scoliometer readings over time is a great way for people with scoliosis to track how their activities are affecting their scoliosis.

After years of using a physical scoliometer or glitchy apps, I developed my own that we use daily at Spiral Spine Pilates Studio. Take a look at what the app looks like on the phone.

To see this tool in action and learn how to use it yourself, you can read my blog on the Scoliometer and watch the how to video included here. Here are links to the items mentioned in the video: Scoliometer Tracking Chart and the scoliometer app I developed [iOS & Android].)

How does scoliosis develop?

“Where does my scoli come from?” It’s the age-old question everyone asks, yet most cannot answer. Interestingly, scoli can be caused by an almost endless number of circumstances or medical conditions. Oftentimes, scoliosis is polycausational, meaning a variety of things caused it.

Doctors and researchers have spent a lot of money and time attempting to determine the root causes of scoliosis. Even with all that research, the question, “where did this come from?” still doesn’t have a definitive answer in many cases of scoli. I’ll lay out a brief explanation of the three most common scoli diagnoses, but encourage you to read my book I Have Scoliosis; Now What? to learn more about how scoliosis develops and figure out how yours developed.

Idiopathic Scoliosis

More often than not, when people talk about scoli, they’re referring to adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS). If scoliosis is found in a patient between 1 and 3 years of age, it’s defined as infantile idiopathic scoliosis. When found between ages 4 and 9, it is considered juvenile idiopathic scoliosis, and when a patient is between 10 and 18 years of age, the diagnosis is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. The majority of scoli cases are adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.

In the medical world, the word “idiopathic” simply means the disease has no known cause. Let’s be honest though—every diagnosis has a cause. AIS is a descriptor of the current condition of someone’s spine, but obviously, it doesn’t give any clues as to what actually caused the 10 degree or higher lateral curve in their spine. I encourage you to seek out what has caused your scoli to develop. My newest book I Have Scoliosis; Now What? can help you on your way to hunting down the root of your scoli; you’ll especially want to look at chapters 12 and 13 for this.

Scroll back up to look at my x-ray and my client’s x-ray to see what idiopathic scoli looks like on an x-ray. Your curves probably aren’t in the exact same place, but you won’t see any signs of functional or congenital scoliosis on these.

Functional Scoliosis

Functional scoli is caused by tension from muscles surrounding the spine. Unlike with AIS, there usually aren’t deep vertebral rotations or genetic components involved. You’ll usually see a “C” curve in the spine with just one curve for functional scoli, instead of two or more curves like you’d see with AIS.

With functional scoliosis, a current biomechanical motion, past trauma(s), or the shape of body parts could be causing the spine to curve. Once you’re able to figure out the root cause, it’s usually relatively simple to get the spine to a more neutral position. The muscular tension around the spine simply needs to be alleviated, and the scoliosis should lessen— or even go away.

Functional scoliosis looks similar to idiopathic scoli when x-rayed. There are no boney malformations. However, you normally only see one “C”-shaped curve as opposed to multiple curves like you see in idiopathic scoliosis.

Congenital Scoliosis

Congenital scoliosis, the scoli associated with prenatal development, is the least common scoli that I have seen. Honestly, it might take less than two hands for me to count the clients and people I know with congenital scoli. Scoliosis develops this way due to malformation of bone before birth. Because a bone developed incorrectly, the bones above and below it are affected in how they are able to rest. For example, a leg length discrepancy or malformed vertebrae can cause scoliosis.

Take this client’s x-ray for example. If you look at the last vertebra (where the pen is pointing), you’ll notice that is is not fully formed affecting how the bones above and below sit. If you affect the bones, you’ll affect the muscles that attach to them. Because of the misalignment, this client has a mild case of scoli.

Muscle Development and Scoliosis

Scoliosis is diagnosed as a lateral bending of the spine 10 degrees or more; however, as we’ve talked about, there are more layers. Muscle development does not take place evenly in those with scoliosis as the spine is not located in the center of the body inhibiting the muscles from working evenly.

Most people’s muscles are beefier and more built up on the convex portions of their curve not matter what type of scoli they have. While they are the longer muscles, they’re usually the workhorse muscles and have been attempting to hold the back upright for many years. The muscles inside the concave portion are shorter and usually more atrophied.

Let’s take the norm of muscle development for scoliosis and turn it on its head. I wrote about Usain Bolt here, who happens to be one of my favorite people living with scoliosis. For the third Olympics in a row he’s won the 100-meter dash and continues to reign supreme as the fastest man in the world. Yes, he has scoliosis if you didn’t know. And no, he has never worn a brace or had surgery.

His back fascinates me, scoli anatomy nerd extraordinaire that I am, because he has trained the muscles in both of his concave portions to be BIGGER than the convex portions. That’s crazy from an anatomical standpoint! Bolt and his trainers clearly know what they’re doing when it comes to addressing his bilaterally uneven muscle development.

How do I build up the correct muscles in my back to halt the progression of my curve? Ah, yes, the million dollar scoliosis question.

Fifteen years of researching and toying around with exercises for different scoli bodies led me to write the books I Have Scoliosis; Now What? and Analyzing Scoliosis; The Pilates Instructor’s Guide to Scoliosis. The first is directed at people with scoliosis and the second at movement teachers. Both have numerous research references, and give you the tools you need to figure out which exercises your unique scoliosis body needs to stabilize its curves.

If you’ve read my books and still have questions, prefer to have your scoliosis analyzed by a professional, or have questions you can’t figure out by yourself? My team and I would be more than happy to help! Book a virtual lesson with us.

I hope that you can confidently answer the question “What is scoliosis” if someone asks you now. Not just the medical definition but also what else comes along with scoli.

___________________________

Erin Myers is an international presenter on scoliosis and founder of Spiral Spine, a company designed to enrich the lives of people with scoliosis. She’s also created a number of scoliosis resources including the books I Have Scoliosis; Now What? and Analyzing Scoliosis, the scoliometer app (iPhone and Android) and many videos. She owns Spiral Spine Pilates studio in Brentwood, TN, which allows her to actively pursue her passion of helping those with scoliosis through Pilates, which she has been doing for over 15 years.